For several reasons, such as disruptive threats, digitalization or blurring industry boundaries, established companies are increasingly forced to create new business opportunities, i.e. to come up with adapted or even entirely new business models. Moreover, developing a ‘business model innovation capability‘ seems particularly vital in the light of ever decreasing life cycles. Shrinking life times of established business models are tied to the fact that benefits of (digitally) transforming those business models are increasingly to be called into question. That said, Clayton Christensen et al. propose:

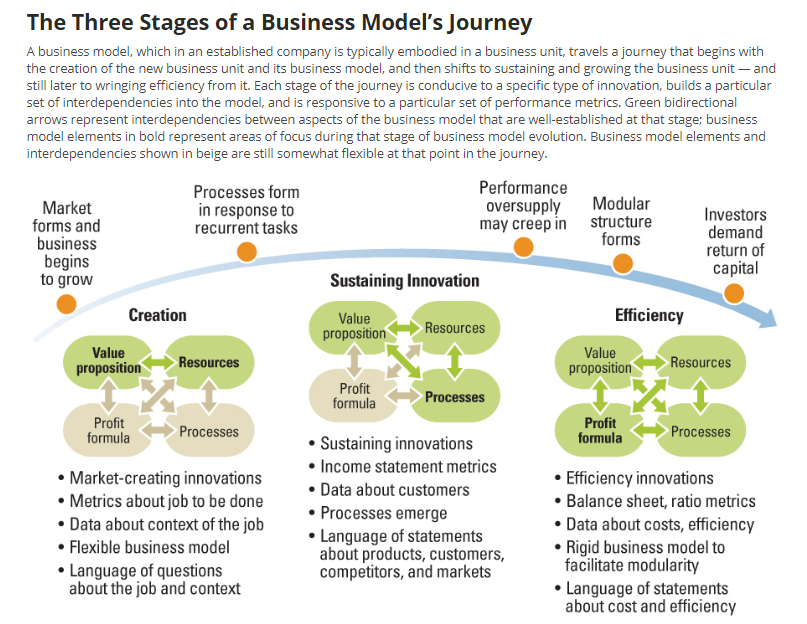

To achieve successful business model innovation, focus on creating new business models, rather than changing existing ones. As business model interdependencies arise, the ability to create new businesses within existing business units is lost. The resources and processes that work so perfectly in their original business model do so because they have been honed and optimized for delivering on the priorities of that model (see also the following chart).

Although the rationale for business model innovation seems to be conclusive, we can find a lot of reasons why companies fail at it. A key question involved in business model innovation is: What is the adequate organizational setting to discover, validate and scale new business models concurrently to running existing (and often still successful) ones? Are they to be separated as dedicated units – even spun out – to unfold and gain traction? Or is an integration with selected units of the core business the best precondition for emerging business models to thrive in a corporate environment?

One is for sure – and this comes as no surprise: There is no one-size-fits-all solution.

Pathways to business model discovery and validation

For the following discussion, let’s delineate the business model innovation process into three generic steps: Discovery – Validation – Scaling. As general guiding principle in the discovery and validation phase, Marcel Bogers et al. advise to not settle too quickly on organizational structure of emerging business models. They write:

The lesson for any organization wanting to explore new business models is to not settle too quickly on a structure for the new business. In fact, the organizational structure can more usefully be thought of as one of the essential building blocks of the business model – that is, as an aspect of the new business that needs to be fully explored and experimented with before you can learn what works best. […]

The business model canvas framework developed by Alexander Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur has become a very popular way to understand the potential building blocks of business models. […] However, organizational designs and the associated organizational tensions that emerge during the process of business model exploration are not well addressed by the existing tools. Companies exploring new business models may not fully recognize that these tensions will almost inevitably emerge and thus may be ill-prepared to manage them. Understanding these tensions should help in managing the challenges of concurrent business models.

Avoiding quick settlement on structure being one of those key areas of tension to be managed, two others have become apparent aside:

- Balance top management support and experimentation

- Power struggle for resources (with existing business model)

To provide the required space, time and support for proper business model exploration, Saul Kaplan has insistently stressed the setup of dedicated Sandboxes – with direct sponsorship of the CEO – as being imperative.

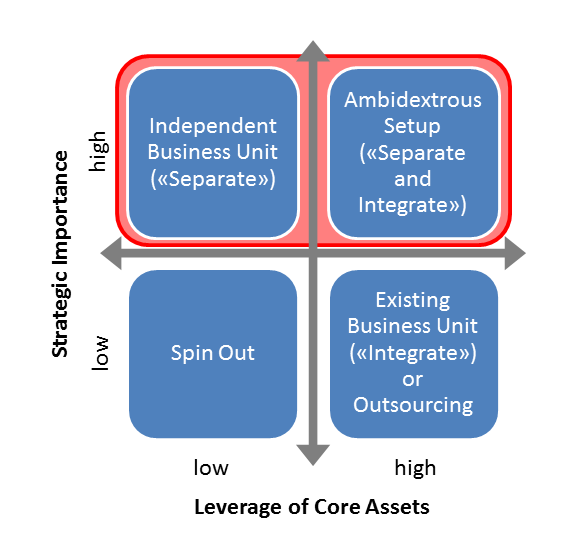

As we have pointed out in a previous post, Charles O’Reilly and Michael Tushman propose to answer the following two aspects to determine the optimal organizational setting for an explorative innovation venture:

- What’s the venture’s strategic importance for the company’s mid and long term (vs. short term) success?

- Can the venture sizeably leverage existing firm assets and capabilities to gain competitive advantage?

Depending on the venture’s particular characteristics, one of four quadrants applies:

In case of strategically important business model innovation, we can therefore conclude that a separated setting turns out indicated for discovering and validating business models, involving more or less linkage with core business units, depending on the characteristics of the emerging business models. We believe that this autonomous business model innovation setup or Sandbox should be accomodated by a (what we call) Exploration Unit, which is organizationally embedded at corporate level and reports to a board member – ideally the CEO. This unit can be declared the owner and place to go for strategically relevant business model innovation.

Pathways to business model scaling

Once an emerging business model has been validated, another question arises: How to further scale it up and what is the best organizational home to pull this off. A useful taxonomy for addressing this issue has resulted from research by Costas Markides and Costas Charitou (2004). The authors outline four distinct pathways to business model scaling, each of which is characterized by the following two key criteria:

- Seriousness of conflicts between emerging and established business model

- Strategic relatedness and similarity of addressed markets (which is closely related to the ‘core asset/capability leverage’ aspect by O’Reilly and Tushman above)

Potential conflicts between new and established business models may arise from the following disparities:

- Disrupting the existing business model

- Cannibalizing the existing customer base

- Destroying or undermining the value of the existing distribution network

- Compromising the quality of service offered to customers

- Undermining the company’s image or reputation and the value associated with it

- Destroying the overall culture of the organization

- Adding activities that may confuse the employees and customers regarding the company’s incentives and priorities

- Defocusing the organization by trying to do everything for everybody

- Shifting customers from high-value activities to lowmargin ones

- Legitimizing the new business, thus creating an incentive for other companies to also enter this market

Strategic relatedness and similarity can mainly be based on three broad categories of strategic assets:

- Customer assets (such as service reputation, customer loyalty, brand awareness and good customer relationships)

- Channel assets (such as access to distribution channels and supply networks and good distribution/network relationships)

- Process assets (such as efficient supply chains for made-to-order or standardized products and services, human capital and the overall skill level of the labor force)

By plotting these two dimensions in a matrix again, the ensuing strategic options for growing new businesses in a corporate setting can be defined:

Separation Strategy

The bigger the conflicts between the two business models and the lower the possibility that the two models can share any synergies among them, the more appropriate is the Separation Strategy.

Case in point: Nestlé (Nespresso), Amazon (Web Services)

Integration Strategy

Often, the new business model presents few conflicts with the existing business model of a firm. In these cases, embracing the new model through the firm’s existing organizational infrastructure may be the optimal strategy. This is especially the case when, in addition to the absence of conflicts, the two business models serve strategically similar businesses and so stand to gain from exploiting synergies among them.

Case in point: Hilti (Fleet Management), Amazon (Prime), Rolls-Royce (Power by the Hour)

Other research suggests that it may be benecicial for organizations to just add a novel business model to the existing one if both are based on complementary, rather than conflicting assets. Incumbent performance after new business model addition tends to improve when the incumbent organization aligns complementary assets (tangible or intangible) through earlier addition of the new business model and conflicting assets with an autonomous unit for the new business model.

Phased Integration Strategy

Under certain circumstances, the most appropriate strategy is to either separate or integrate the new way of competing, but not right from the start. For example, when the new business model serves a market that is strategically similar to the existing business but the two ways of competing face serious conflicts between them, the firm faces a difficult challenge: on the one hand, it stands to benefit if it integrates the two and exploits the synergies between them; on the other hand, integration might lead to serious internal problems because of all the conflicts. In such a case, it might be better to separate for a period of time and then slowly merge the two concepts so as to minimize the disruption from the conflicts.

The main challenge a company faces that chooses the Phased Integration Strategy is to keep the new unit sufficiently autonomous but also prepare it for the eventual incorporation.

Case in point: Schwab (e.Schwab: build-up of online brokerage beside brick-and-mortar business), Lan & Spar Bank (build-up of direct banking alongside branch network)

Phased Separation Strategy

When the two business models do not conflict with each other in any serious way but the markets they serve are fundamentally different, the firm faces another interesting challenge. On the one hand, given the lack of conflicts, it could integrate the new model with the existing organization without much difficulty. On the other hand, integration will not bring many benefits and might even constrain the development of the new way of competing into a viable business for the firm. In such a case, it might be better to first transfer the new business from the exploation unit and build it inside the organization first so as to leverage the firm’s existing assets and experience before separating it into an independent unit.

The main challenge a company faces that chooses the phased separation strategy is to prepare a growing unit for divorce.

Case in point: Daimler (car2go)

Business model innovation comes down to reconciling separation and integration

No matter if the preferred generic strategy proves to be separation or integration, we have to bear in mind: In the end, an optimal organizational approach ends up being an adequate balance:

- Even if a firm decides to separate the emerging business model, it must still find ways to exploit its existing strengths in the new unit

- Even if a firm decides to integrate the emerging business model (i.e. to benefit from synergies), it must still find ways to give the new business enough freedom to grow on its own

With that said, the question that needs to be asked is not: Should we separate (integrate) or not? But rather: What activities do we separate, and what activities do we keep integrated?

Markides and Charitou finally conclude that several variables can influence how well a new business model is managed in each of the four matrix quadrants. For example, companies that adopt a Separation Strategy will do better if they

- give operational and financial autonomy to their units but still maintain close watch over the strategy of the unit and encourage cooperation between the unit and the parent through common incentive and reward systems

- allow the units to develop their own cultures and budgetary systems

- allow each unit to have its own CEO who is transferred from inside the organization (rather than hiring an outsider)

Similarly, companies that adopt an Integration Strategy will do better if they

- designate a top management sponsor in the organization who holds the power to protect the new business from interference by the parent

- treat the new business model as a wonderful new opportunity to grow the business (rather than see it as a threat)

- leverage the strengths of the traditional business to find ways to differentiate themselves (rather than imitating the strategies of their attackers)

- approach the task in a proactive, strategic manner rather than as a hasty knee-jerk reaction to a problem

- take extreme care not to suffocate the new business with the existing policies of the firm

Takeaway

There is no single best way to choosing the adequate organizational pathway to discovering, validating and scaling new business models and growth opportunities in corporate settings. Encapsulating the previous findings, corporate business model innovation ventures are to be assessed along the following key criteria:

- Strategic and operational relatedness of the new business model to the existing core business model(s)

- (Potential) Leverage of core assets and capabilities for the business model innovation venture

- Seriousness of (potential) conflicts between emerging business model and existing business model(s)

Combinining the degrees of those characteristics, the major organizational pathways to corporate business model innovation can be depicted in the following framework:

No matter if the resulting pathway focuses on separation or integration, it can be boiled down to managing the key trade-off to corporate innovation: Separating the venture adequately to secure essential autonomy and protection, while at the same time integrating all activities that exhibit significant synergies with the existing core business.

6 Responses to Organizational Pathways to Business Model Innovation