This is part one of a two-parts article co-written with Kevin McFarthing from Innovation Fixer. The second part can be found here.

Facing increasingly dynamic and unpredictable environments, firms are required to develop convenient innovation strategies, constantly adapt them to changing conditions and properly implement strategically-aligned initiatives throughout their organizations. Innovation portfolio management (IPM) can act as the pivotal tool to translate strategic objectives and priorities into project-based innovation activities. Furthermore, it provides a framework to convert raw ideas into real investment opportunities, based on their risk profile.

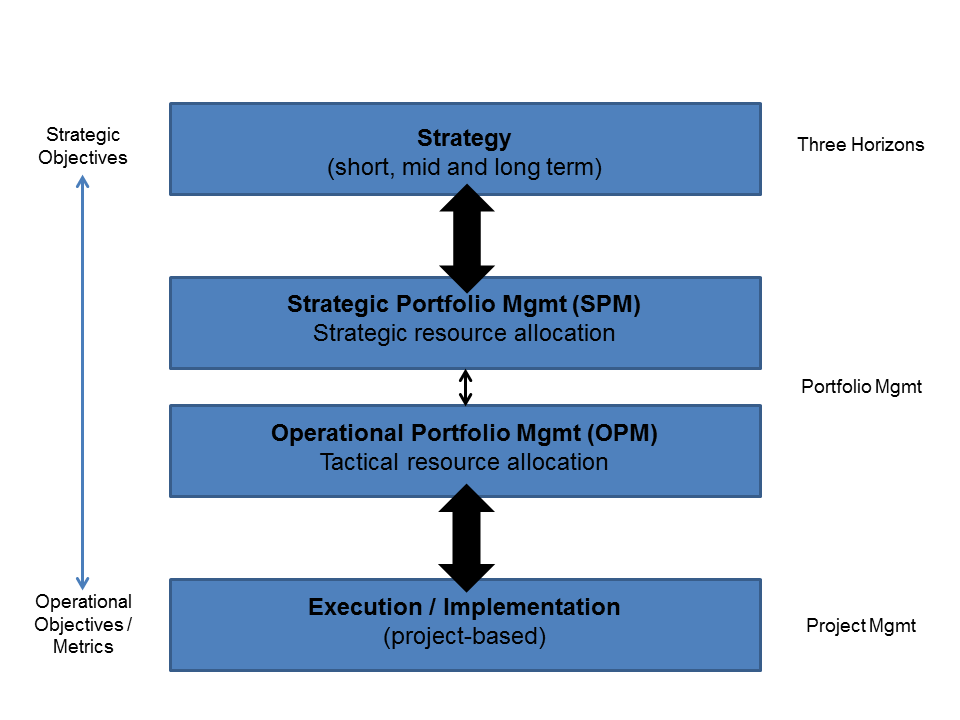

Here, we introduce the concept and give some ideas on how IPM can be implemented in the organization. IPM can be divided into a strategic and an operational part. Strategic Portfolio Management (SPM), covered by the first part of this article, makes sure the right innovation initiatives are pursued (“doing the right things”) and backed with resources. The second part outlines Operational Portfolio Management (OPM), aimed at successfully executing the selected projects (“doing things right”).

Integrating strategy and execution via portfolio management

Uncertainty and rising levels of complexity make it impossible for companies to precisely determine the future. Recent research [Rita Gunther McGrath: The End of Competitive Advantage: How to Keep Your Strategy Moving as Fast as Your Business, Harvard Business Review Press (2013)] indicates that the notion of a sustainable competitive advantage is likely to be abandoned. Strategy today needs to align to a more fluid nature of business environments. It has to be flexible enough to adapt constantly to changing external and internal conditions, even though the aspiration to serve shareholders remains constant.

Key issues for companies to succeed in these highly dynamic and interconnected marketplaces are:

- Continuous integration of strategy development and refinement with execution to deliver tangible results. Many companies struggle, not because they haven’t any suitable strategy in place, but because they fail to translate it into adequate initiatives and integrate it across the organization.

- Allocation of scarce resources and capital across a range of initiatives to maximize value, while reducing risk for the entire company. Due to resource constraints, only 5-10% of project requests can actually be realized in practice.

Establishing a portfolio management system can address these issues. Portfolio management is positioned as a “transmission belt” between qualitative strategy definition and metrics-based project execution (figure 1). It ensures that the critical requirements of SPM and OPM are integrated.

Figure 1: Portfolio management as integrator of strategy definition and project-based execution.

Like a more conventional strategy, portfolio management is best driven by a corporate center or project management office (PMO) and a supportive senior management. The hallmark of a portfolio management approach is the willingness to continuously assess and optimize the portfolio. Portfolio management can be defined as balanced planning and steering of a portfolio of initiatives, aiming to provide the highest overall value for the entire company. This process can be enhanced by using IT-based platforms. The portfolio is frequently assessed according to qualitative and quantitative criteria:

- What is the project’s contribution to corporate strategy? (qualitative and quantitative)

- What is the project’s associated risk level? (qualitative)

- What is the project’s expected financial return? (quantitative)

As research suggests, there seems to be some upside performance potential around this topic for most companies. The 2013 survey of 800 members of the PMI (Project Management Institute) showed that only a small proportion of respondents believe their organizations are “mature” in their practice of project (17%) and portfolio (12%) management. This stark observation came in a context where more projects are being delayed; since 2008, the percentage of projects that project managers say have met their original goals and business intent has declined 10 percentage points (from 72% in 2008 to 62% in 2012).

Using portfolios in the context of innovation management also requires following balances to be managed:

- The innovation portfolio is required to cover both short-term and long-term initiatives.

- It needs to feature a variety of initiatives in the portfolio without losing focus.

Balancing short-term and long-term innovation

Innovation is required to lead to short-term returns through optimization of existing products, services and business models. However, it also plays a central role to secure long-term survival by exploring new territories, whether geographic or new business. Many companies unintentionally harvest their core business through pushing short-term performance while losing out on long-term investments to stay ahead of the game. Sustainable innovation management must therefore be targeted at identifying and developing future businesses in parallel to optimizing current ones. Successfully integrating different time horizons turns out to be an imperative in innovation management. Related to this balance, simultaneous management of incremental and radical innovation via ambidextrous organizational setups is crucial to build a dynamic innovation capability.

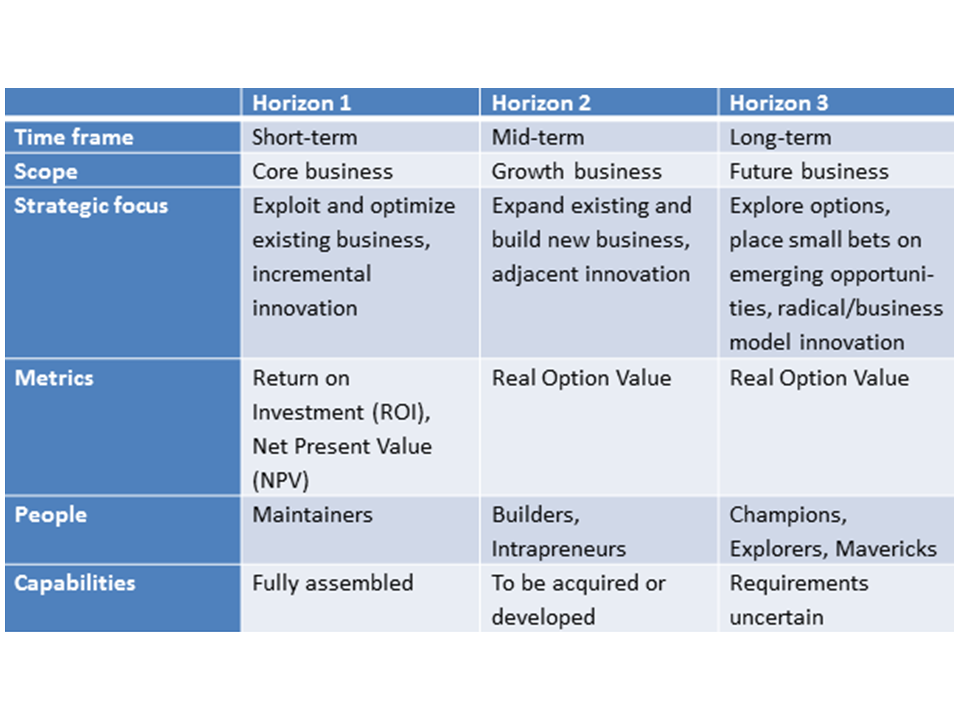

The “three horizons” can serve as a convenient model to categorize and manage innovation initiatives across different time frames. The characteristics of the different innovation horizons can be taken from table 1.

Table 1: Characteristics of the three innovation horizons

Table 1: Characteristics of the three innovation horizons

Innovation portfolio management needs to carefully pay attention to Horizon 2 activities. This is “strategy’s no-man’s-land” between short-term budgets and long-term focus [Geoffrey A. Moore: To Succeed in the Long Term, Focus on the Middle Term, Harvard Business Review (2007)]. Horizon 2 efforts must be insulated and isolated from core business until it can produce material revenues (which, depending on the size of the company, possibly range from $50 million to $100 million). This particularly involves enforcing portfolio commitments by blocking resource migration across horizon boundaries. During this adolescent phase, such projects require customized processes, metrics and performance targets.

Case in point: IBM

IBM acts as a prime example on how the introduction and pursuit of a balanced innovation portfolio enhances overall innovation capability, adaptability and organizational ambidexterity [Charles A. O’Reilly, J. Bruce Harreld, Michael L. Tushman: Organizational Ambidexterity: IBM and Emerging Business Opportunities, California Management Review (2009)]. In September 1999, Lou Gerstner (then CEO of IBM), was reading a monthly report that indicated that current financial pressures had forced a business unit to discontinue funding of a promising initiative. He asked: “Why do we consistently miss the emergence of new industries?” IBM’s strategy group also confirmed that the company had failed to capture value from 29 separate technologies and businesses. A detailed analysis revealed that IBM’s mistake had been an unwitting focus on Horizon 1 and 2 businesses to the exclusion of Horizon 3. Interviews with senior managers confirmed this conclusion.

Armed with this understanding, IBM decided to balance their portfolio by identifying and implementing experimental Horizon 3 initiatives, the “Emerging Business Opportunities” (EBO) program. In 2000 there were seven EBOs, including Linux, Life Sciences, Pervasive Computing, Digital Media, Network Processors and e-Markets. Since their inception, 25 EBO’s have been launched by 2009. Three of these have failed but the remaining 22 produced well more than 15% of IBM’s revenue at this time. The defined criteria to move from an EBO to a separate growth business were:

- a strong leadership in place

- a clearly articulated strategy for profit contribution

- early market success

- a proven value proposition

The process has since been more decentralized so that separate lines of business develop their own EBOs. Throughout the company, they are used to extend capabilities and to scale business models.

Balancing variation and focus of innovation initiatives

As the future is hard to foresee, firms need to be comfortable with experimentation, i.e. testing new technologies, products and business models. A recent study [Adi Alon, Wouter Koetzler, Steve Culp: The Art of Managing Innovation Risks, Accenture, http://www.accenture.com/us-en/outlook/Pages/outlook-journal-2013-art-of-managing-innovation-risk.aspx] has identified portfolio management as one major area to manage innovation risks adequately. Proper risk management enables experimentation, being conducive to radical and breakthrough innovation and counteracting the tendency to “play safe” by solely supporting incremental innovation. This involves spreading small bets across various innovation options, expecting that some of them turn out to produce large returns and cover the investment required for experimentation. And since a portfolio of experimental initiatives prepares for various future conditions, it’s obvious that not all of the initiatives will become relevant and return value. Indeed, as in nature, variation appears to be a major precondition for successful adaptation in changing environments. However, in order to avoid spreading commitment, resources and capital too thinly across too many and too diverse initiatives, it’s mandatory for organizations to focus on underlying, more predictable, drivers that are shaping business environments (such as digital technology progress, aging population or emerging market development). Since these fundamental forces will over time shape a broad array of surface events, developing indicators may help anticipate upcoming scenarios and therefore constrain the number of indicated experiments and initiatives. According to John Hagel, this can be considered a strategy paradox: in a time of increasing change and uncertainty, we must be clear on what will not change to not get distracted.

Strategic Portfolio Management

As outlined above, strategic portfolio management translates innovation strategy into an aligned project portfolio. The portfolio is reviewed on the basis of defined criteria. Typically, a Portfolio Management Board (PMB) is in charge for this strategic decision making. The PMB should include those executives that can best decide on the strategic alignment as well as the executives that are responsible for the resources involved. The PMB’s main tasks are:

Periodic evaluation and prioritization of the entire innovation portfolio

The innovation portfolio is periodically assessed by means of strategic, financial and risk-related criteria. In most cases, scoring methods are used for this assessment. Based on the evaluated criteria, projects are re-prioritized, or stopped in case minimum requirements are not met. It’s important that evaluation and prioritization is carried out in a transparent and consistent manner for the entire portfolio. However, the evaluation process should also allow for exceptional reasons to fund an initiative that doesn’t meet the required numbers. These reasons and well-informed decisions need to be communicated transparently throughout the organization as well. From a practitioner’s point of view, prioritization should be carried out in groups (e.g. “top 5”, medium etc.), rather than as a sequential numbered list.

One major advantage that comes along with the introduction of a portfolio approach is the ability to adapt to changing conditions. As prioritization criteria and assessment of individual projects may change over time, frequent reviews allow adjusting the organization’s directions of impact.

Managing a portfolio of innovation initiatives should obey one central principle: evolutionary selection. The decision on whether or not to scale up an initiative, e.g. a new technology or business model, is made when further information has been gained from the previous project stage. Much of this needed familiarity can come only through experimentation and testing, rather than from vision or analysis. This suggests staging investments across the innovation portfolio depending on the associated risk and uncertainty. Therefore, big bets are usually made in horizon 1, medium bets in horizon 2, whereas the high-risk profile of activities in horizon 3 suggests making little bets. This highlights the importance of pilot projects, prototypes and iterative market-testing and -learning before initiatives become scaled up.

Indeed, research [Bansi Nagji, Geoff Tuff: Managing Your Innovation Portfolio, Harvard Business Review, http://hbr.org/2012/05/managing-your-innovation-portfolio/] reveals: firms that allocate in average 70% of their innovation funds to incremental innovation (short-term), 20% to adjacent innovation (mid-term) and 10% to radical/breakthrough initiatives (long-term) outperform their peers, typically realizing a P/E premium of 10% to 20%. The individual allocation depends on industry, competitive position and the firm’s stage of development (figure 2).

Figure 2: Innovation portfolio matrix across the three horizons. The size of the circle represents the project’s economic value. Portfolio management follows a staging investment from horizon 3 (uncertainty) towards horizon 1 (familiarity).

Strategic and priority-based resource allocation

As the prioritization of the portfolio is supposed to show impact, resources are required to be allocated accordingly. This sounds self-evident – but isn’t always in practice. Portfolio prioritization and resource management (on a strategic level) should be fully aligned. A feasibility check that decisions and priorities are backed with the needed resources is mandatory. Strategic resource management is about including resource availability constraints into the analysis of alternative portfolio compositions. If a portfolio proposal will overload the available resources, this can either affect the portfolio composition (delay or abandon projects) or the resource pool size (e.g. by hiring or open innovation). In order to give tactical resource allocation (as part of OPM) a fair chance of succeeding, strategic resource allocation must be coupled with the strategic portfolio management process.

Release and exit of innovation initiatives

The selection of new, strategically-aligned initiatives has to be carried out with due diligence. Particularly in turbulent times or in face of crises this is often not the case, known as: doing things for the sake of doing things. Due to a variety of influence factors, interdependencies and stakeholders, portfolio management features a high complexity. In order to maximize value-creation for the company, the PMB needs to make sure these conditions are properly taken into consideration and initiatives are assessed with relevant and up-to-date criteria. It is also responsible for consequent termination of unattractive or unsuccessful initiatives.

In part two of this article, we’ll discuss Operational Portfolio Management (OPM), where the portfolio directs resource allocation, metrics and reporting.

This article was first published at InnovationManagement.se.

6 Responses to Managing Innovation Portfolios – Part 1: Strategic Portfolio Management