Research shows that growth fueled through organic innovation is more profitable than growth driven by acquisition, in part because the organizational capability required is vastly different. But the litmus test is: How can established organizations build successful new businesses through corporate entrepreneurship, also referred to as Intrapreneurship, on an ongoing basis? This is also one of the key questions that companies we’ve been working with are raising more frequently.

What is Intrapreneurship?

First, let’s be clear on what Intrapreneurship actually means. According to Robert C. Wolcott and Michael J. Lippitz the term is defined as the process by which teams within an established company conceive, foster, launch and manage a new business that is distinct from the parent company but leverages the parent’s assets, market position, capabilities or other resources. It differs from corporate venture capital, which predominantly pursues financial investments in external companies. Although it often involves external partners and capabilities (including acquisitions), it engages significant resources of the established company, and internal teams typically manage projects. It’s also different from spinouts, which are generally constructed as stand-alone enterprises that do not require continuous leveraging of current business activities to realize their potential.

Four generic models spanned by two dimensions

Wolcott and Lippitz offer a useful taxonomy, encompassing four generic Intrapreneurship models that can be differentiated along two dimensions, both of which are under direct control of management: The first dimension is organizational ownership: Who, if anyone, within the organization has primary ownership for the creation of new businesses? (Note: Responsibility and accountability for new business creation might be focused in a designated group or groups, or it might be diffused across the organization.) The second is resource authority: Is there a dedicated “pot of money” allocated to corporate entrepreneurship, or are new business concepts funded in an ad hoc manner through divisional or corporate budgets or “slush funds?”

Together this generates the following (2×2)-matrix, including the following types:

- Opportunist

- Enabler

- Advocate

- Producer

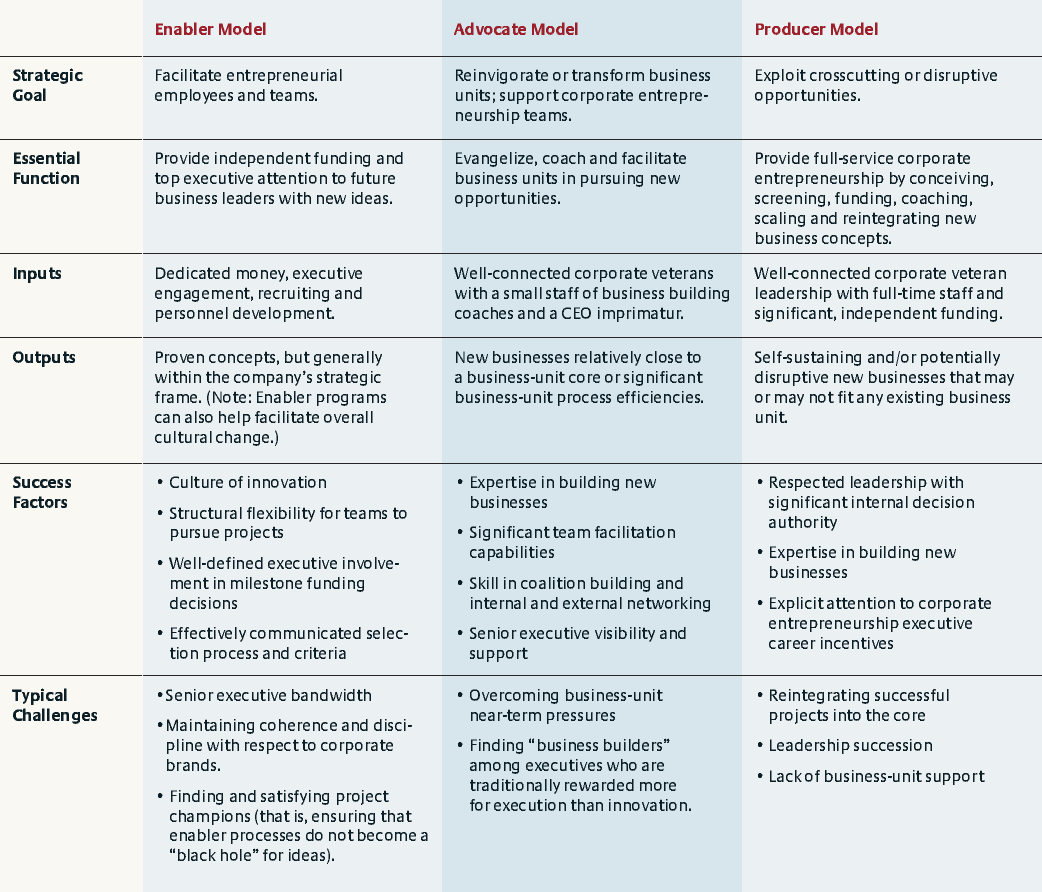

Each model represents a distinct way of fostering intrapreneurship. Particularly in large corporations, multiple models can be supported concurrently at different levels and functions. The opportunist model, however, works well only in trusting corporate cultures that are open to experimentation and have diverse social networks behind the official hierarchy (in other words, places where multiple executives can say “yes”). Without this type of environment, good ideas can easily fall through organizational cracks or receive insufficient funding. Consequently, the opportunist approach is undependable for many companies. Therefore, the following table characterizes only the remaining three models in more detail:

Employing the right model

Which model proves well-suited and is to be selected strongly depends on the questions: Which purpose and objectives are to be pursued by implementing an intrapreneurship model in the company? Is it geared towards nurturing companywide cultural change, reshaping a particular business division or exploring cross-company, occasionally even disruptive, opportunities.

Enabler programs can support efforts to enhance a company’s culture. When an organization already enjoys substantial collaboration and ideation at the grassroots level, the enabler model can provide clear channels for concepts to be considered and funded. For companies seeking cultural transformation, enabler processes in combination with new hiring criteria and staff development can result in a number of employees becoming effective change agents. The enabler model is particularly well-suited to environments in which concept development and experimentation can be pursued economically throughout the organization.

For companies that want to accelerate the growth of established divisions, the advocate model might be the best option. Because of the limited resources of this model, managers must tailor their initiatives to the interests of existing lines of business, and employees have to collaborate intensively throughout the organization. This enhances the potential fit of opportunities to a company’s operations, but also requires leadership to ensure that projects do not become too incremental. Advocates exist to help business units do what they can’t accomplish on their own but should pursue in order to remain vital and relevant. Moreover, the advocate model (as well as the producer model) can prevent corporate entrepreneurship from becoming a casualty of powerful business units or competing silos.

If a company seeks to conquer new growth domains, discover breakthrough opportunities or thwart potentially disruptive competition, then it should consider the producer model. In general, business units are not likely to pursue disruptive concepts, and they often face strong near-term pressures that discourage investments in new growth platforms. The producer model helps overcome this, and it can provide the necessary coordination for initiatives that involve complex technologies or require the integration of certain capabilities across different business units.

Each of the models requires different forms of leadership, processes and skill sets. An enabler model depends on establishing and communicating simple, clear processes for selecting projects, allocating funds and tracking progress, all with well-defined executive involvement. Advocate models require individuals with the instincts, access and talent to navigate the corporate culture and facilitate change. Leading advocate organizations build an arsenal of facilitation methodologies, new business design tools and networks with external capabilities. The producer model requires considerable capital and staffing and a direct line to top management. Understaffed, part-time or underfunded producer teams are set to fail.

Takeaway

Embedding intrapreneurship programs in corporate innovation management follows ‘One size doesn’t fit all‘. Selecting the right approach, or rather the apt combination, factors in intended and distinct directions of impact. Drawing on the previously introduced Model for Modern Dual Corporate Innovation Management, the following areas of application can be given for the different models:

- Enabler: Fostering innovation culture and intrapreneurial mindset/behavior throughout the entire organization (enabling foundation)

- Advocate: Adapting and extendening existing business units (stream: Adapt, playing field: H2)

- Producer: Exploring and scaling novel opportunities, (yet) outside of the business units’ scopes (stream: Scale, playing fields: H3/H2)

As the three of them turn out largely complementary, this suggests considering putting those models in place concurrently on the part of most organizations – in order to stimulate the highest impact on internal innovation capabilities.

[…] June 2017, Ralph-Christian Ohr wrote about four models of intrapreneurship innovation. Where he focused on what specifically fuelled […]