This is the second part of a post co-written with Thierry De Baillon from Sonnez en cas d’absence. Read the first part here.

A striking change of focus in the social business arena occurred during the last five years. Despite the fact that Andrew McAfee’s original definition specified its scope as «within companies, or between companies and their partners or customers», infant Enterprise 2.0 was mainly concerned by internal collaboration. The teaser from one of the major events of this early period, the Boston 2007 Enterprise 2.0 Conference, talked about “(…) the technologies and business practices that liberate the workforce from the constraints of legacy communication and productivity tools like email“.

This somehow navel-gazing vision of firms, obsessed by internal processes and employees’ performance, has shifted toward a customer-centric attitude. Apart from acknowledging that organizations more and more see the benefits, if not the imperative, to operate as connected ecosystems, including partners, suppliers, customers, and even competitors, in their value creation mechanisms, this profound change mirrors the evolution of our understanding of the way business is done in our hyper-connected era. Yet, putting such a strong emphasis on customers, on their needs and expectations, is at risk of obscuring the role played by other stakeholders. Creating, and sustaining, customers requires more than broadening our traditional array of interaction channels. It requires more than engagement, more than co-creating products and services with them. As developed in the first part of this post, businesses need to develop the ability to reinvent themselves. In order to be able to address unmet and changing customers’ needs, they are required to adjust value creation through new business models.

On the external facing side, social business is proving day after day its relevance in better meeting the new challenges of marketing. On the internal side, beyond present focus on collaborative project management and observable work, it provides an appealing and natural framework to support the flip side of the coin of organizational core functions: innovation.

The marketing view: visualizing and reducing the dynamic tension

Business, social or not, is all about creating, delivering and capturing value, or, in short, about a business model. In “The Business Model Innovation Factory“, Saul Kaplan perfectly summarizes how these points articulate themselves together:

“Business models are designed to create value for a customer or end-user.

(…) One of my favorite ways to describe how a business model creates value is by first answering the question, what is the job the customer is hiring your company, product, or service, to do?

(…) An operating model depicts core capabilities necessary to deliver value and how they are linked to each other. It enables a shared story of how an organization works together across functions and with its partners to deliver value.

(…) A business model story describes who pays and how much for value delivered. It outlines a profit formula for the business based on the required operating cost structure in relation to revenue as well as the capital requirements to finance both fixed assets a working capital to support ongoing operations and growth.”

In other words, value is co-created by enterprise and its customers, in the sense that “Value co-creation is bringing in your own contextual resource to achieve the beneficial outcomes with the firm at the point of consumption/experience (remember, we are still talking about value-in-use?)”

In our hyper-connected world, where customers are interacting, trying to find the best solution to fulfill their job-to-be-done, the search for value (their search, as well as the one from companies) creates a dynamic tension between both parts, as motivations between them and companies profoundly differ. Visualizing and reducing this tension requires new skills and capabilities. As Irving Wladawsky-Berger writes: “Customer value is different. This requires a complementary set of management competencies, much softer or people-oriented in nature, including a focus on human capital, strategy, decision making, innovation and social skills.” This also requires a new operational and managerial model, focusing on engagement with customers, listening, real-time interaction, and fast sense-and-respond loops. Fundamentally, this requires to organize, behave and operate as a social business.

Dion Hinchcliffe recently drew (conceptually as well as literally, and his drawings are always impressive) a map of the Operations of a Social Business. The only flaw we can see in this map is the point of view he drew it from: the engagement level. Bringing social business to strategic level doesn’t require C-level adhesion to the necessity of engagement or to the benefits of co-production of products and services, but maybe simply changing the lens of our vision: the primary benefit from a social business is to allow companies to dynamically adjust their value proposition to customers’ needs and expectations. To put it simply, social business is a perfect fit for present business models improvement.

The innovation view: leveraging new business skills

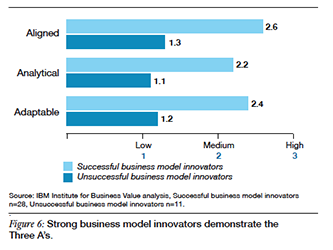

As important as improving an existing business model can be, the real challenge, and opportunity, for organizations lies in their ability to explore and develop new business models, as we exposed in the first part of this post. In a follow-up to its Global CEO Study 2008, entitled “Seizing the Advantage“, IBM has identified three key characteristics demonstrated by successful business model innovators: they are all Aligned, Analytical and Adaptable.

By becoming social, organizations will acquire the necessary structure and capabilities to be able to maximize each of the “Three A’s”:

- Aligned – Leverage core capabilities and enforce consistency across all dimensions of the business model, both internally and externally, that build customer value.

As said above, one of the key consequences of becoming social is allowing proper adaptive alignment between customers’ needs and organizations’ value proposition, and facilitates the exploration of novel propositions and business model hypotheses.

- Adaptable – Link innovative leadership with the ability to effect change and create operating model flexibility. Outperforming innovators are capable of and willing to pursue new opportunities while maintaining focus on sustaining current business -often referred to as ambidextry.

There is quite a consensus on the role leaders should play in a collaborative enterprise. They should work at empowering their employees and at giving them enough autonomy and support, what Vineet Nayar, vice chairman and CEO of HCL Technologies Ltd and author of “Employees First, Customers Second”, resumed it as “CEOs, Get Out of the Way!”. But as seducing as this anthem sounds, it only works where no business model innovation is required, or at least where minor tweaks suffice, letting line managers adjusting according to internal/external interactions. A better role for leaders is the one of “business architect” (and we suspect Mr Nayar in reality to assume this role), dynamically orchestrating the required sets of resources. As Stephan H. Haeckel wrote:

” Designing a business as an adaptive system of roles and accountabilities makes it possible to change business models much more rapidly. Those parts of an enterprise that can and should be designed for efficiency can be dispatched as easily as can the capabilities designed for adaptiveness. This is because roles are linked in terms of outcomes, not in terms of the way in which the outcomes are achieved. How a given role should be designed depends on the degree of predictability in the requests made of it and is a decision to be made by the accountable individual occupying that role. Because a business architect need not specify how things are to be done, he or she can incorporate roles that vary widely in terms of their internal processes and even management systems. This feature makes the incorporation of external capabilities a natural part of any business design.”

- Analytical – Use information strategically to create foresight, and prioritize actions while measuring and tracking for rapid course correction.

In Harold Jarche‘s words: “in trusted networks, openness enables transparency, which in turn fosters a diversity of ideas. Supporting the creation of social networks can increase knowledge-sharing which can lead to more innovation, especially in networks built on trust.” Knowledge sharing, capture of tacit knowledge, recombination of existing knowledge to create new patterns, are at the core of social collaboration. A study conducted in 2011 by Institute for the Future for Apollo Research Institute identified ten critical work skills needed in the next ten years. Among them, sense-making (described as “ability to determine the deeper meaning or significance of what is being expressed”), computational thinking (the “ability to translate vast amounts of data into abstract concepts and to understand data-based reasoning”) and cognitive load management (the “ability to discriminate and filter information for importance, and to understand how to maximize cognitive functioning using a variety of tools and techniques”) directly deal with analytical capabilities in a networked organization.

The systemic view: a structural framework for business model innovation

Set alone, these “Three A’s” are necessary, but not sufficient characteristics to drive successful outcomes. As we outlined, business model innovation requires embracing emergent strategies while following an adaptive path to keep on adjusting present models, all of which equating to dealing with a wicked problem.

In “What’s the problem? An Introduction to Problem Structuring Methods“, Jonathan Rosenhead has exposed some principles to be applied when tackling wicked problems, principles which were summarized by Tom Ritchey as follows:

- Accommodate multiple alternative perspectives rather than prescribe single solutions

- Function through group interaction and iteration rather than back office calculations

- Generate ownership of the problem formulation through transparency

- Facilitate a graphical (visual) representation for the systematic, group exploration of a solution space

- Focus on relationships between discrete alternatives rather than continuous variables

- Concentrate on possibility rather than probability

A culture of diversity, transparency through narration of work, and complex interaction throughout an organization’s ecosystem are core characteristics of a social business. By reconciling the marketing with the innovation view of the collaborative enterprise, organizations will arm themselves with all the capabilities needed to increase value co-creation. By organizing for flexibility, subsidiarity and connectedness, they will become able to internally orchestrate these capabilities in order to reinvent themselves as needed. As Dave Gray stated: “Design for connection is design for companies that are made out of people. It’s design for complexity, for productivity, and for longevity.”

As highlighted in IBM’s study (see diagram below), organizations must combine organizational improvement (exploitation of existing business model) and reinvention (exploration of new business models) to adapt to different paces of change in their environment. To do so, they have to integrate and balance the marketing and the innovation views in a more systemic and emergent approach to corporate strategy.

Social businesses are designed for business model innovation. They are complex adaptive systems designed for auto-(re)organization and resilience, and form a structural framework for innovation, at all levels. But they are only part of the story. To gain real business model agility, organizations must cultivate a culture of experimentation, favoring decision-making through fast prototyping and testing. Present, and next generation technology focuses on the marketing view: Social CRM, Adaptive Case Management and big data analytical tools are about to complete the set of social technologies available today. Tomorrow’s breakthrough enterprise-grade technologies might well be complex decision-making support tools, and Problem Structuring Methods implementation, to help organizations in better tackling the wicked problem of business model innovation and reinvention.

[…] This is the first part of a post co-written with Thierry De Baillon from Sonnez en cas d’absence. Read the second part here. […]